A strong U.S. dollar and over-leveraged banks in emerging markets threaten to derail exports to emerging markets, but you can overcome these obstacles with creative and flexible financing.

Compared to the last decade, the value of the U.S. dollar is strong compared to most foreign currencies—and that’s a problem for U.S. exporters to emerging markets.

A strong dollar forces foreign customers to pay more for American-made goods, making them less competitive than foreign-made alternatives.

Overleveraged banks in emerging markets exacerbates the problem, as these banks can struggle to supply the necessary capital to importers—and an increase in the price of U.S.-made goods can stretch those systems beyond their lending capabilities.

Little Changes, Major Impact

The dollar’s relative strength against other currencies hit a 14-year peak on January 3, 2017. Since then, the dollar has given back some of that strength, with the WSJ Dollar Index (BUXX) falling 8.1% for 2017. Still, the dollar remains strong compared to the last decade, the BUXX index rising nearly 25 percent from 2008 to 2018.

“Little price increases on products and little increases in the cost of borrowing have a big impact on what companies in developing markets can buy,” says Carson Strickland, Senior Vice President for Global Trade Finance at Regions Bank. In response, importers place smaller orders and miss payment deadlines.

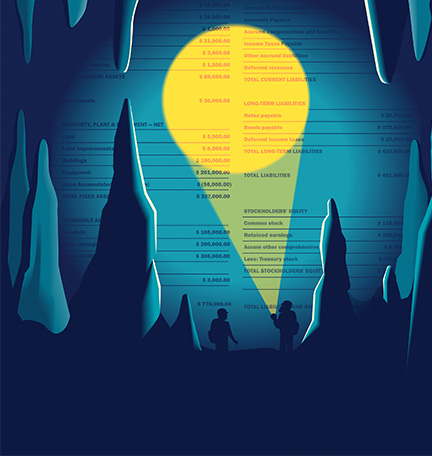

In addition, excess lending and high leverage in developing countries make it more difficult for companies to finance imports. In India, banks have $150 billion “stressed” loans that total more than than 15 percent of bank assets. And the delinquency rate for loans 90 days or more overdue in Brazilian banks is around 3.5 percent—a sign borrowers cannot service debt, making them less likely to find the funds to import American goods. (By comparison, nonperforming loans in the United States comprised 1.17 percent in the third quarter of 2017).

Ignorance Is Not Bliss

However, Strickland says there are strategies that can help minimize risk for U.S. exporters. One option is to shift the sales focus toward domestic customers or exports to developed markets. However, ignoring emerging markets isn’t a compelling long-term growth strategy.

“If [exporters] are really trying to grow their businesses for the long run, they have to penetrate the markets that are growing the most, which are emerging markets in regions such as Asia and Latin America,” according to Strickland.

“There’s plenty of purchasing capacity in the U.S. and Europe and most of the developed world,” Strickland says, “but those markets aren’t really growing quickly.”

Strickland says companies can focus on two strategies that can enable their exports to emerging economies: offering special financing and doing business in foreign currencies.

Special Financing

As national financial institutions in emerging nations lack liquidity to finance large expenditures, a problem exacerbated by the strong dollar, American exporters should consider taking those emerging-market banks out of the picture.

For example, a telecommunications company in Asia was having difficulty affording imports from a Southeastern U.S. lumber company, a Regions client. The lumber company worked out a deal that gave the Asian telecom provider a year to pay for purchases; credit insurance from another bank backed the transaction.

Doing Business in Foreign Currency

Another way for American companies to lessen their customers’ foreign-exchange risk is to sell their products abroad in local currency. Doing so means assuming currency-conversion rate risk, but that may be worthwhile if the alternative is declining revenue. “You’re taking that exposure off the hands of your buyer so that they’re not having to deal with it,” Strickland says.

One Regions client, an Arkansas farmer, noticed that a Mexican customer was stretching its payment terms in hopes for a more favorable exchange rate. The farmer reached an agreement with the Mexican customer to bill in pesos in exchange for larger orders and more timely payment, and the farmer mitigated its currency risk with a forward contract locking in the exchange rate.

Ultimately, what does this mean for American companies who are looking for opportunities abroad? While a strong dollar creates challenges for U.S. companies that export to emerging economies, Strickland says, exporters can overcome those challenges with a little creativity and financial flexibility.