Threats unthinkable 20 years ago are now a major problem for global security and stability. With terrorism and asymmetrical warfare now common, how is the defense industry coping?

Whoever coined the phrase “arms race” in the early 20th century likely had in mind the type of battlefield engagement that has defined warfare for most of history.

But today, the emergence of a wildly divergent group of threats ranging from urban campaigns against non-state forces, from cyberattacks to the ongoing threat of traditional invasions means that the global arms race is no longer just about better weapons or having more of them. For defense manufacturers, it means developing weapons for a broader range of engagements.

Although the absolute numbers remain high, military investment as a share of the world’s collective gross domestic product dropped from 5.8 percent in 1967 to 3.8 percent in 1986, and to 2.2 percent in 2016, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Tighter budgets have placed a premium on efficient solutions, and the United States military is searching for new tactical advantages in an era in which its sheer size and technological prowess is less than in the past.

“Warfare has broadened, but there’s a very limited amount of capital you can spend to address that expanded range of threats,” says Greg Jones, Managing Director of Regions’ Defense Banking Group and Regions Securities. “A major theme you see within the U.S. military is finding a way to be as efficient as possible with that capital.”

For defense manufacturers, that means innovating in multiple directions. Urban warfare, for example, is a rapidly evolving category — a 2017 Rand Corporation report highlighted the emerging value of advances in armor, short-range missile defense, and tunnel warfare in urban conflicts, even as the renewed threat of nuclear war makes headlines around the globe.

As America Goes, So Goes the Global Defense Sector

America sets the tone for the global defense sector, both as its biggest spender and as home to its largest suppliers. The U.S. military accounts for 36 percent of global military spending ($611 billion in 2016). Its manufacturers hold an even more dominant position in the sector: They account for two-thirds of global defense revenues, according to Deloitte, led by firms such as Lockheed Martin, Boeing, General Dynamics and Northrop Grumman.

Two major priorities of the American military are greater operational efficiency and next-generation tactical advantages, Jones says. The former includes a continued and increasing reliance on outsourcing, which includes contractors for a large share of what Jones calls “non-kinetic” functions like mission-support services, IT, and base operations.

“Short of pulling the trigger, we’ll see a lot more military functions performed by contractors,” he says. A related priority is increased support for foreign proxy forces, fighters trained and equipped by the U.S. military. The effort to build a next-generation tactical advantage, which the Obama administration dubbed “the Third Offset,” remains a priority as well.

As an example of emerging weapons that demand counter-development, Jones points to tech such as short-range, warhead-enabled drones that soldiers can carry to the battlefield. It may be an effective, devastating weapon — but that destructive power works for terrorists as for the U.S. military.

“We’re going to see a lot of focus on developing technology to disable, disrupt, destroy unmanned aerial vehicles that might be used by an enemy,” Jones says.

The development of unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs — as well as the ability to counter them — are both big, big growth markets. The missile defense systems used to contend with emerging nuclear threats are also ripe for innovation. Jones says that such systems are still early in development.

“Today, there’s a high degree of probability that we could shoot down one missile,” Jones says. “But if an enemy can fire 10 missiles and all of those missiles have multiple reentry vehicles — multiple different warheads that come down — then the fear is that something like that would overwhelm any type of missile defense system that we have today.”

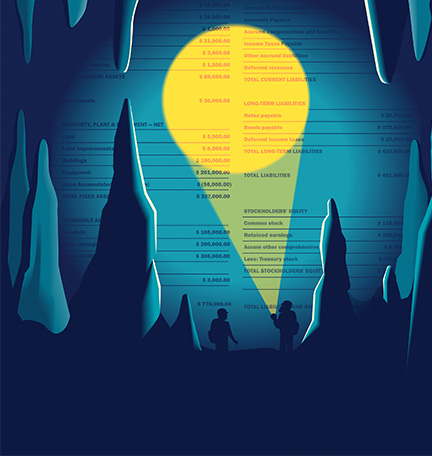

Defense Contractors: Buying Research

Due to these emerging threats, the focus is on research and development, and this emphasis is turning major weapons manufacturers into acquirers.

On the supplier side, big U.S. defense contractors are signaling their willingness to dive into M&A. Falls Church, Virginia-based Northrop Grumman acquired aerospace manufacturer Orbital ATK for $7.8 billion in September. Shortly after the deal was made public, Chicago-based aerospace and defense giant Boeing announced that it, too, was on the prowl for acquisitions. One factor influencing the growth is relaxation and streamlining of regulations governing weapons exports, a reform begun during the Obama administration and embraced by President Trump.

Greater Tensions, Greater Defense Budgets

Despite the overall reduction of defense budgets as a percentage of GDP, rising tensions around the world are expected to drive up defense expenditures globally, especially in Asia and the Middle East, according to a 2017 Deloitte forecast. Western European nations are spending more as well, with budgets increasing 2.6 percent in 2016, owing to a perceived threat from Russia, according to PwC.

There’s also a “Donald Trump effect” at play: Even though a 2011 budget sequestration law has limited the American president’s ability to radically increase defense spending (Trump’s 2018 budget allocates $603 billion to defense, a $54 billion increase over 2016 but only $18 billion more than Obama’s planned 2017 increase), the president’s influence is at work in Europe. After Trump pushed NATO’s 29 member countries to increase their defense spending, the group announced a $12 billion spending increase by its non-U.S. members, to about $295 billion.

That increase in spending doesn’t mean that more conventional weaponry gets pushed aside for newer more advanced defense systems that deal with emerging threats. No, it actually means that the funding and research focus must be spread out to different types of projects and equipment.

“It’s not like we can take the resources we once devoted to traditional weaponry, and now just use them for asymmetric conflicts instead,” Jones says. “You still need aircraft carriers and tanks, so even as you turn your attention to these asymmetric type of situations, you have to continue to be prepared for force-on-force engagements.”