It’s the stuff of business legend: When Jack Stack and his partners purchased engine remanufacturer SRC in 1983, the division of International Harvester seemed doomed. It was hemorrhaging money, had a crippling debt load, and morale was in the pits.

With everything on the line, Stack hit on a novel idea: Share the numbers with employees, teach them what they mean—and how they relate to each and every job—and give everyone a stake in the company’s success.

So was born open-book management (OBM), or as Stack calls it, the Great Game of Business. SRC succeeded spectacularly, and OBM has become embedded in the lexicon. But is such dramatic transparency right for every company?

Here’s a look at the core tenets of OBM, their advantages, and potential pitfalls:

- Transparency is a tool for engagement, not the endgame. “The goal is to create a sustainably excellent company that provides opportunities for employees and for everyone involved,” says Bill Collier, a St. Louis-based consultant affiliated with The Great Game of Business who has run two companies with the system. “Transparency is necessary to achieve that goal.” The Great Game process centers on three intersecting circles, Collier explains. “The first is letting people know what’s important; the second is how you, the employee, help achieve those goals, and the third is your stake in the outcome—what’s in it for you. This includes only job security and benefits, but in our practice, sharing in a bonus pool when the company exceeds its goals.” At the intersection of the three spheres is the “critical number,” the metric that links each job to the company’s strategic direction.

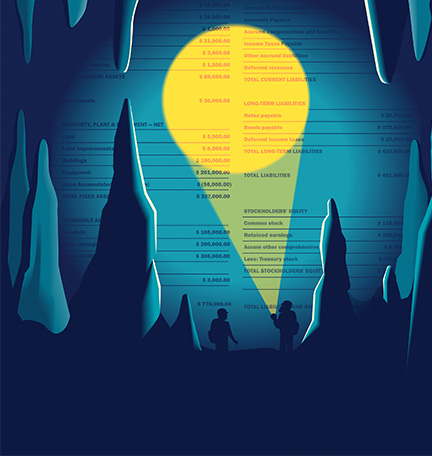

- Open book does not mean full disclosure. Typically, Collier says, a company will combine accounts in its P&L to a limited number of top-line items when presenting to employees. Not only does this make it easier for people to digest, but it also keeps sensitive information—such as individual compensation—invisible. At the same time, however, numbers aren’t the only things being shared. Strategy, too, is laid out for everyone to see, understand and hopefully, implement.

- There’s a steep learning curve. As you might expect, employees at all levels require no small amount of training in order to understand how the business operates. The payoff, however, is significant: First and foremost, they see how a metric that they or their group controls can affect the bottom line. “If you hire a guy to put a nut on a bolt, he may understand that he has a goal of 100 bolts a day, but he won’t know why that’s important,” says Collier. “More significantly, he has no incentive to produce 120, even if he’s capable of doing so.” But by directly linking performance metrics to strategic goals and profitability, even front-line workers can see how their labor benefits not only the company, but themselves as well.

- It requires discipline. Certainly a major concern among executives contemplating an open-book system is disclosing sensitive information to employees, but another stumbling point, Collier says, is the discipline required in “committing to running the business by the numbers, doing the forecasts, and sticking with it religiously,” for example holding the regular “huddles,” or meetings in which performance, forecasts, and progress is shared. “There’s a lot of preparation involved, and less dedicated companies can let it slip if top management isn’t committed.”

When implemented strategically and rigorously, radical transparency can transform a company into a workforce of motivated “intrapreneurs.” But the first step is the biggest: finding the courage to share not only the goals with employees, but the road map as well.